And, finally, here is the conclusion of this series on my journey along the Trail of Tears.

New Echota Historic Site | Calhoun, Georgia

The last site that I visited along the National Historic Trail, in many ways, should have been the first. The New Echota Historic Site is both the literal and historic starting point for the Trail of Tears. From 1825 until the Cherokee’s removal, New Echota, located in northeast Georgia, was the capital of the Cherokee Nation. It was the site of Cherokee government, and as such, in addition to the houses of those who lived there, it hosted the Council House and Supreme Court of the Cherokee Nation, along with a print shop that printed the first newspaper in an Indigenous language, the Cherokee Phoenix. Of course, New Echota also gave its name to the infamous Treaty of New Echota, the document drafted by the breakaway band of Cherokees that sealed the fate of the entire nation, making their forced removal an inevitability. As explained earlier, the Treaty of New Echota gave the Georgia state government all the legal veneer they needed to proceed with their ethnic cleansing. When soldiers and settlers began rounding up Cherokee at gunpoint and forcing them from their homes, New Echota also became the site of Fort Wool, one of many camps used to concentrate the Cherokee before they began the journey westward.

Today, New Echota is a state historic site administered by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources. The site’s official website invites visitors to “celebrate the cultural legacy of the Cherokee People while discovering the innovations, political sophistication and the daily life of the residents of New Echota, Capital of the Cherokee Nation, where the Cherokee removal on the Trail of Tears officially began.” The site, which is open six days per week, features “12 original and reconstructed buildings, including the Council House, Court House, Print Shop, Missionary Samuel Worcester’s home, and an 1805 store, as well as outbuildings such as smoke houses, corn cribs and barns.”

The New Echota Historic Site was not part of my first journey along the Trail of Tears. When we took that trip in 2014, we started in Chattanooga, Tennessee, where the Cherokee were transported after state and federal troops rounded them up before they began their walk westward. I realized after that trip, however, that my experience of the Trail should have started elsewhere. When examining any act of genocide or mass atrocity, it is always essential to start earlier—not from the moment of violence and death, but from the life and community that existed before. It is only by starting here that we can understand exactly how resonant violence functions, how one group of humans can gradually progress to the attempted annihilation of another group of humans, and how the violence continues to disrupt social and political structures in the aftermath of mass killing. In the case of the Cherokee, New Echota, as a symbolic space, offers a fascinating picture of that “before.” As I would learn on my first visit to the site in December 2016, however, the New Echota Historic Site as it exists today also offers an illuminating view of how this past violence against the Cherokee is understood by settler society today, as well as how that violence resonates in contemporary US society.

When visitors come to the New Echota Historic Site, they first pass a series of memorials to the Cherokee in front of the visitors’ center. A single tree stands tall in front of the center, alongside a plaque that reads, “Planted Oct. 29, 1988 in memory of the 4,000 Cherokees who died on the Trail of Tears – 1838.” The tree stands alongside a traditional, stone monument to the Cherokee, which is surrounded by four flags: the flag of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma; that of the Eastern Band of the Cherokee, which is formed largely from the descendants of those who avoided removal by hiding in the mountains; and that of the United Keetowah Band of Cherokees, who are descended largely from those Cherokee who had already migrated to what is today Oklahoma several decades before the forced removal. Flying over all these three flags, on a pole that is several feet higher, is the United States flag.

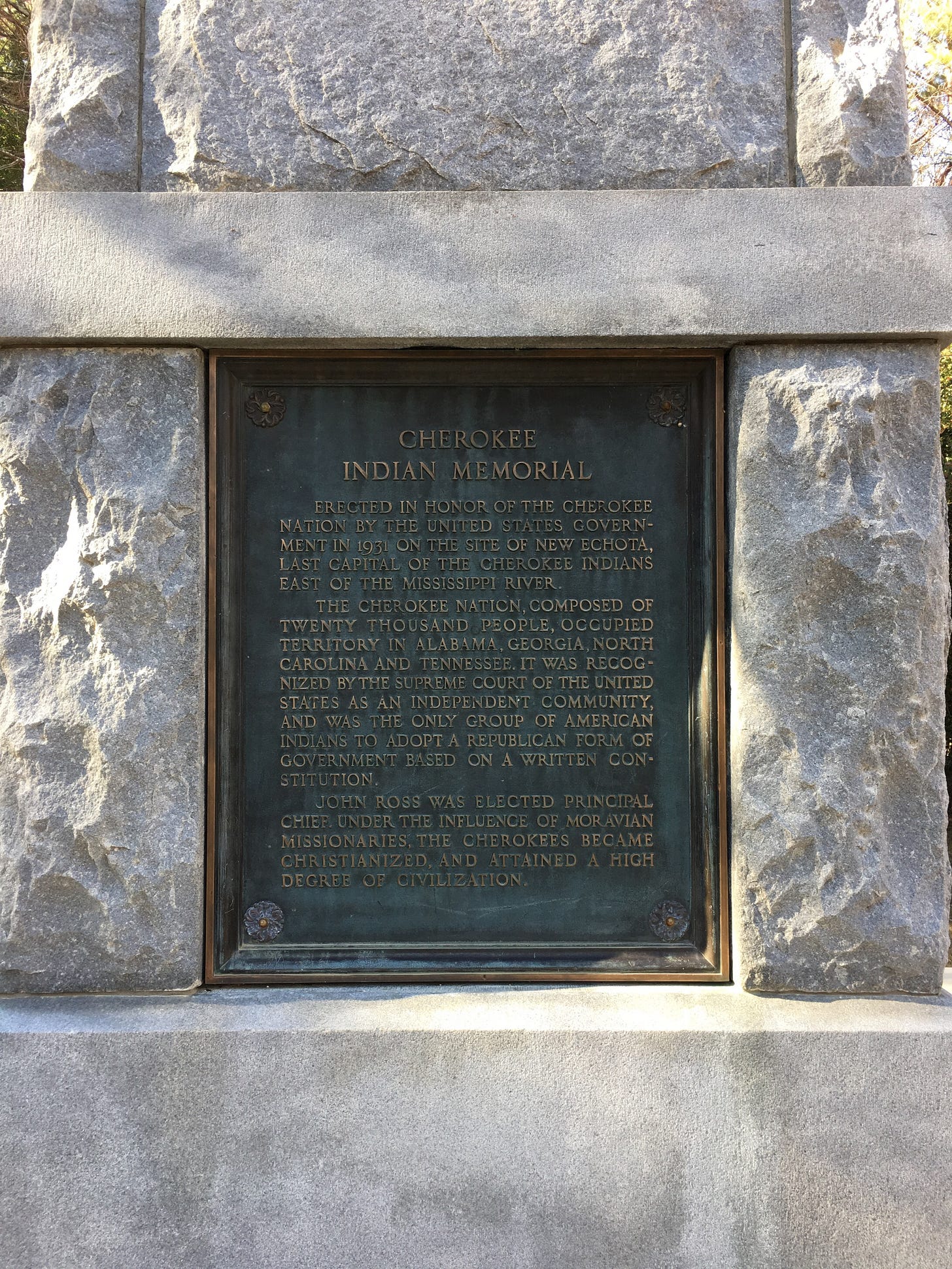

The irony of the US flag flying above the flags of these three Indigenous nations is obvious. Here, in a site that is supposedly recognizing the atrocities perpetrated against the Cherokee by government forces, the flag of the perpetrator still stands above all others. The plaque on the stone monument in between these flags explains that this monument was erected by the US government in 1931. No responsibility is taken for the crimes committed. Instead, the plaque reads as follows:

The Cherokee Nation, composed of twenty thousand people, occupied territory in Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina and Tennessee. It was recognized by the Supreme Court of the United States as an independent community, and was the only group of American Indians to adopt a republican form of government based on a written constitution. John Ross was elected principal chief. Under the influence of Moravian missionaries, the Cherokees became Christianized, and attained a high degree of civilization.

The problems with this inscription are evident but are still worth nothing. First, designating the Cherokee as “occupying” territory frames this Native population as an invasive force, claiming land that was not already their own. Moreover, the plaque valorizes the Cherokee to a certain extent, but only because of the degree to which they assimilated. Their form of government and their acceptance of Christianity mark them as somehow different from other Indigenous groups. Indeed, the assimilationist character of the Cherokee is not only a focus on this plaque from 1931, but one that is reiterated throughout the New Echota Historic Site, as I will explain. Furthermore, the syntactical structure of the final sentence reiterates an age-old colonialist narrative: first, “the Cherokees became Christianized,” then, they “attained a high degree of civilization.” The structure of the sentence places these two events in a linear and causal relationship, where one led directly to the other. Consequently, it reinforces the idea that the latter, in fact, is not possible without the former.

Inside the visitors’ center, a small exhibition explains key historical moments relating to New Echota, including the founding of the Cherokee Phoenix. A map displays the gradual and continual reduction of Cherokee territory from the colonial period through removal, and one display case holds a copy of the New Testament written in Cherokee. A short film entitled “The Cherokee Nation: The Story of New Echota” introduces visitors to New Echota, offering historical context for the grounds they will explore. The film, produced in 1990, consistently stresses the high degree of adaptation to settler culture demonstrated by the Cherokee. Within the first minute of the film, the narrator declares:

The Cherokee adopted much of the white culture, becoming the most progressive of all American Indian tribes. They learned English, attended schools, and adopted a new way of dress. Cherokee men became farmers, politicians, and businessmen. They used tools such as the plough, saw, axe, frow, and adze. […] Metal tableware and European ceramics graced many Cherokee dinner tables.

The tone of the narrator conveys to the visitor that she is expected to be impressed by the levels of “civilization” achieved by the Cherokee. The film evokes the use of farm tools as a source of amazement in the same way an anthropologist might discuss the use of tools by homo erectus. And, of course, the term “progressive” is analogized to “white culture,” reproducing a common narrative that paints Indigenous cultures as completely lacking in civilization before the arrival of European colonists. Similarly patronizing language is reproduced throughout the film.

Toward the end of the film, when the narrator begins recounting the Trail of Tears itself, the film also reverts to a familiar trope. After describing the hardships of the Trail, the narrator states, “They traveled by wagon, horse, riverboat, and on foot. The process was slow, the winter a severe one. By the completion of the removal in the spring of 1839, sickness, hunger, and heartbreak has caused 4,000 deaths along the way.” Here, we see a common tendency in depicting both Indigenous death at the hands of settler colonialism generally and the Trail of Tears in particular. Deaths were caused by “sickness, hunger, and heartbreak” and by a severe winter, rather than by the government officers and white settlers who forced the Cherokee to emigrate. Focusing on these natural elements makes the 4,000 deaths appear more like deaths by natural disaster than an orchestrated plan by the settler state. The passive voice of these statements removes the perpetrator from the picture. As a result, the death of the Cherokee still appears tragic, but the agency of the individual people and the state machinery that made the deaths a reality are completely erased. It is as if an earthquake or hurricane wiped out these 4,000 Cherokee—not the US government.

Furthermore, the film’s focus on the degree to which Cherokee life resembled settler life underscores an unspoken idea that the Trail of Tears is a tragedy only because the victimized population were not, in fact, “savages,” but had achieved a level of Christianization and “civilization” that should have prevented such treatment. In doing so, the violence experienced by every other Indigenous nation in the US, including those that had resisted adaptation to settler ways of life, and including even the other four tribes forcibly removed through the Indian Removal Act, is somehow diminished, painted as less of an atrocity. In fact, no other Indigenous nation is mentioned at the New Echota Historic Site.

Outside the visitors’ center, the grounds of the historic site reflect, in many ways, the vacuum of life that resulted from the forced removal of the Cherokee. The grounds are mostly empty, apart from a handful of reconstructed buildings. The Cherokee Council House, the home of the Cherokee Nation’s legislative branch, has been rebuilt, as has the Supreme Court. Visitors can enter these impressive and well-maintained structures and, through the information and sound installations provided within, can get a real sense of how these halls of government functioned. A reconstructed shop and tavern paint a picture of social life at the height of New Echota, and a reconstructed farmstead depicts the realities of the Cherokee farmer during the pre-removal period. The only original structure still standing on the grounds is the house of missionary Samuel Worcester, a staunch ally of the Cherokee who, among other acts, translated the Bible into Cherokee and, more importantly, served as the eponymous plaintiff in the US Supreme Court case for Cherokee sovereignty, Worcester v. Georgia (1832).

Aside from this handful of physical structures, however, the grounds convey a heavy sense of absence. One sign in the middle of a vacant field reads “Town Street,” marking where the main thoroughfare of New Echota once crossed. Today, it is just part of a vast, empty field, with only the barest traces of a pathway evident. Four stones marking the corners of a former foundation and another sign mark the location of Elias Boudinot’s house, the site of the signing of the Treaty of New Echota. Despite these signs and structures, the overwhelming feeling generated by the New Echota Historic Site is one of absence.

This absence was not only one of buildings, but also of people. Of course, there is the absence of the Cherokee, the traditional holders not only of New Echota, but all northwest Georgia. But there is also a great absence of visitors to the site. Tibi and I visited New Echota in December 2016. We were the only people at the site during our entire, multi-hour visit. I spoke with the Georgia park ranger managing the site on the day of our visit, asking him about attendance. He did not have an exact number of annual visitors, but he pulled out a large ledger where the rangers recorded the number of visitors to the site for each day and month. For most months of the year, the numbers ranged from 100 to 150. One month had as few as 65 visitors. The winter (when we were there) marked the lowest months of attendance, he said. The previous July saw more than 500 visitors to the site. Given these numbers, a generous estimate would be that between 2,000-3,000 people visit the site each year. Although these numbers seem remarkably low, they appear in line with many of the sites along the National Historic Trail. Throughout my research on the Trail, it was not uncommon to be the only visitor to each site.

Conclusion

The Trail of Tears National Historic Trail is an essentially ambivalent space. At times, it recognizes the violence of settler colonial genocide, and in doing so opens opportunities to respond to that violence productively. The Crabb-Abbott Farm, for instance, is one example of how this initiative has facilitated new forms of public action to recognize the crimes of settler colonialism. At other times, however, sites along the Trail simply reproduce the violence—a reality most markedly present in the near erasure of genocidal violence at the Hermitage, which opts instead to celebrate a perpetrator.

In many ways, this ambivalent quality of the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail echoes a broader US American reality relating to Indigenous peoples, past and present. What I realize, however, is that this tension also aligns with my own personal experience of emotional ambivalence as I traveled the Trail. I was at once on a journey to discover more about one of the darkest pages in American history, as well as to document how these sites reflect a national understanding of that history. But at the same time, I was enacting one of the most quintessential US American experiences, a great American road trip, with two people I loved. And we had a great time doing it. Ultimately, this ambivalence reflects the paradoxical realities of the United States itself. We are, after all, speaking of a country that continues to use Native American stereotypes as the mascots of its sports teams, defending them as a celebration of Native culture. It is a place where the President can call someone “Pocahontas” as an insult, and it does not lead to any large-scale outcry. It is a country that was founded on a demand for life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, and yet it was built on the dual atrocities of Indigenous genocide and the enslavement of millions.

In 2018 the First Nations Development Institute published a study entitled Reclaiming Native Truth. Their report included the findings garnered from focus groups, interviews, and surveys of nearly 15,000 people across the United States, as well as the analysis of nearly five million social media posts. Their findings highlight this ambivalent relationship with Native culture in the United States. For instance, their report finds that, for most non-Indigenous Americans, Native peoples are invisible in the present, with 62% of Americans reporting that they are unacquainted with Native Americans. The researchers write, “Into this void springs an antiquated or romanticized narrative, ripe with myths and misperceptions,” that depicts Native Americans as of the past, not of the present. The study also finds that non-Indigenous peoples consistently “hold concurrent yet conflicting views” about Native peoples, including that they are:

• Both poor and flush with casino money

• Both spiritually focused and struggling with alcohol and drugs

• Both resilient and dependent on government benefits

• Both savage warriors and noble savages

• Both caring of the land and living in trash-filled and polluted reservations

• Both separate from and part of U.S. culture.

Clearly, ambivalence and contradiction lie at the core of contemporary US American understandings of our relationship to Native peoples. It is this same contradiction that led Ojibwe author David Treuer to call reservations “the paradoxically least and most American place in the twenty-first century.” The disparity that exists among the sites I have described along the National Historic Trail only serve as further examples of this complexity.

According to the First Nations Development Institute, however, “shifting the narrative about Native peoples demands that we fully understand current public perceptions and the dominant narratives that pervade American society.” Accepting this challenge, rather than neatly resolving this troubling ambivalence, I end this series by claiming (or hoping, at least) that it may be more productive to sit within the discomfort it produces, dwelling in a space that Dominick LaCapra calls empathic unsettlement.

According to LaCapra, it is possible to exist within a space that at once acknowledges the trauma of the other without appropriating it as one’s one, therefore absolving oneself from the responsibility to act in the face of the trauma of others. He calls this space empathic unsettlement, writing,

At the very least, empathic unsettlement poses a barrier to closure in discourse and places in jeopardy harmonizing or spiritually uplifting accounts of extreme events from which we attempt to derive reassurance or a benefit (for example, unearned confidence about the ability of the human spirit to endure any adversity with dignity and nobility).

The space of empathic unsettlement is one in which both emotion and knowledge can coexist in a way that opens a space for action. To be empathetically unsettled involves not only a recognition of the trauma experienced by the victim but also a willingness to sit in the discomfort of that trauma, without attempting to whitewash it, move beyond it, or resolve it in any way. Or, rather, without asking the victim to do the work of resolution. Instead, the onus rests in the listener or observer, who can resolve the discomfort by working actively to change the forces that brought that discomfort about.

Of course, the term ‘empathic unsettlement’ is especially appropriate in this case. The Trail of Tears is a historic event that literally unsettled the Native body, forcing it to resettle itself outside the bounds of the settler state. In the same way, traveling the Trail today offers an opportunity to generate a more figurative unsettlement, an empathic unsettlement, through which non-Native subjects can sit in their own discomfort with the historic and contemporary violence from which they continue to benefit.

Traveling the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail offers an opportunity to encounter the pain and violence experienced by Native peoples in the US. To be empathetically unsettled by this experience, however, means to encounter that trauma without appropriating it as one’s own. In this scenario, the problematic spaces along the trail—the spaces that reproduce some of the violences rather than redress them—provide opportunities for visitors to resist a sense of closure, to resist the urge to place that violence as fully past. This work requires intention, however. It is unlikely that it will happen spontaneously. It requires education, so that visitors know to look at spaces like these with a critical eye. It requires self-reflexivity that prevents visitors from separating themselves from the stories with which they are engaging. And it requires conviction, so that encounters with memory spaces lead to behavior changes, to action, for it is only through action that true change can be effected.

This new remembrance can come in part from sitting in the discomfort of empathic unsettlement. And yet, even as one resists the urge to celebrate unduly, as LaCapra puts it, “the ability of the human spirit to endure any adversity,” it remains important to acknowledge that the Trail of Tears ends in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, where the Cherokee Nation is headquartered today. Even if the genocidal project of settler colonialism is ongoing, it has not succeeded. Cherokee peoples and other Native peoples around the country are still here. Just as it is essential to recognize the enduring violences of settler colonialism, it is equally important that one does not think of settler colonialism as an eschatological mandate that the Native body cannot escape. Maori scholar Brendan Hokowhitu writes, “Indigenous theorizing cannot fully develop without the possibility for existential agency, for I do not want to believe that the atrocities of colonization were the defining point at which the existential potential of the Indigenous body remains scarred indeterminately.”

Herein lies the real challenge: finding the balance between empathy that does not allow for closure or grand narratives of human resilience, along with a worldview that does not foreclose the agency and potential of Native peoples. It is my hope that the ambivalence offered by the experience of traveling the trail, along with my reading of that journey, is a potential starting point for generating that other ambivalent state of empathic unsettlement, especially for those who continue to benefit from the enduring violence of settler colonialism today.