I’ve neglected my weekly posts for a couple of weeks now, and I apologize for that. Things at work have gotten a bit overwhelming, and I couldn’t find the time and energy to draft new travel essays.

Recently, however, I remembered a piece of travel writing that still hasn’t seen the light of day, despite the fact that it’s something I’m really proud of. My first book, Resonant Violence: Affect, Memory, and Activism in Post-Genocide Societies, was published a few years ago. In its final form, it includes five chapters and a conclusion. What most of the tens of readers of that book don’t know, however, is that it was originally supposed to have a sixth chapter that I had to cut because I had exceeded my contractually obligated word count. That chapter was about a trip I took with Tibi and our friend, Caitlin, along the infamous Trail of Tears and the conflicting emotions we had on a fabulous and fascinating road trip encountering some of the most depressing moments of US history.

The chapter is way too long for one post, so I’m going to break it up into a series of posts. I’ll also spare you all the majority of the academic theory, though some of it will certainly be impossible to extricate. Still, I hope you find it interesting. I’m certainly glad to be able to put it out into the world (finally)! Here we go…

In the fall of 1838, the first of roughly 16,000 Indigenous Cherokee who had been rounded up at gunpoint and concentrated into camps near the Tennessee River in what is today the city of Chattanooga began a 1200-mile journey westward. Most walked the entire way. They walked until they left the boundaries of what was then the United States. Thousands died, especially children and the very old. Those who survived joined others in what is today Oklahoma. At the time, it was simply referred to as “Indian Territory.” This event, the most infamous act of ethnic cleansing to occur on US territory, was known by the Cherokee as ᎯᏍ ᏅᎾᏓᎤᎸᏨᏱ [“Nunahi-Duna-Dlo-Hilu-I”], or “The Trail Where They Cried,” though it has now come to be known as the Trail of Tears.

The term “Trail of Tears” most commonly refers to the forced removal of the Cherokee people from the southeastern United States to the west, which took place in 1838-39. In fact, the Cherokee were not the only tribe to walk such a trail; four other tribes in the American Southeast faced a similar fate in the early 1830s: the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee, and Seminole peoples. Together, these five tribes were known by the settler colonists as the “Five Civilized Tribes” because, of all Native tribes, they were the ones to embrace settler/European cultural practices more than any other. Within these five tribes, it was common to speak English, live in European settler-style housing, and dress in the same clothing that the settlers wore. The Cherokee drafted their own constitution, modeled after the US Constitution, which sought “to establish justice, promote our common welfare, and secure to ourselves and our posterity the blessings of liberty.” They became so assimilated within southern settler society that some who could afford it began purchasing slaves to work their homesteads.

The fact that the Cherokee assimilated so thoroughly makes their eventual removal seem all the crueler, even paradoxical. In the end, the fact that the “Five Civilized Tribes” so clearly assimilated into settler society only served to highlight for the settlers the singular difference that could not, in their minds, be assimilated: their race. This reality, combined with a more practical desire for their lands and the resources they contained, led to their forced removal to the west.

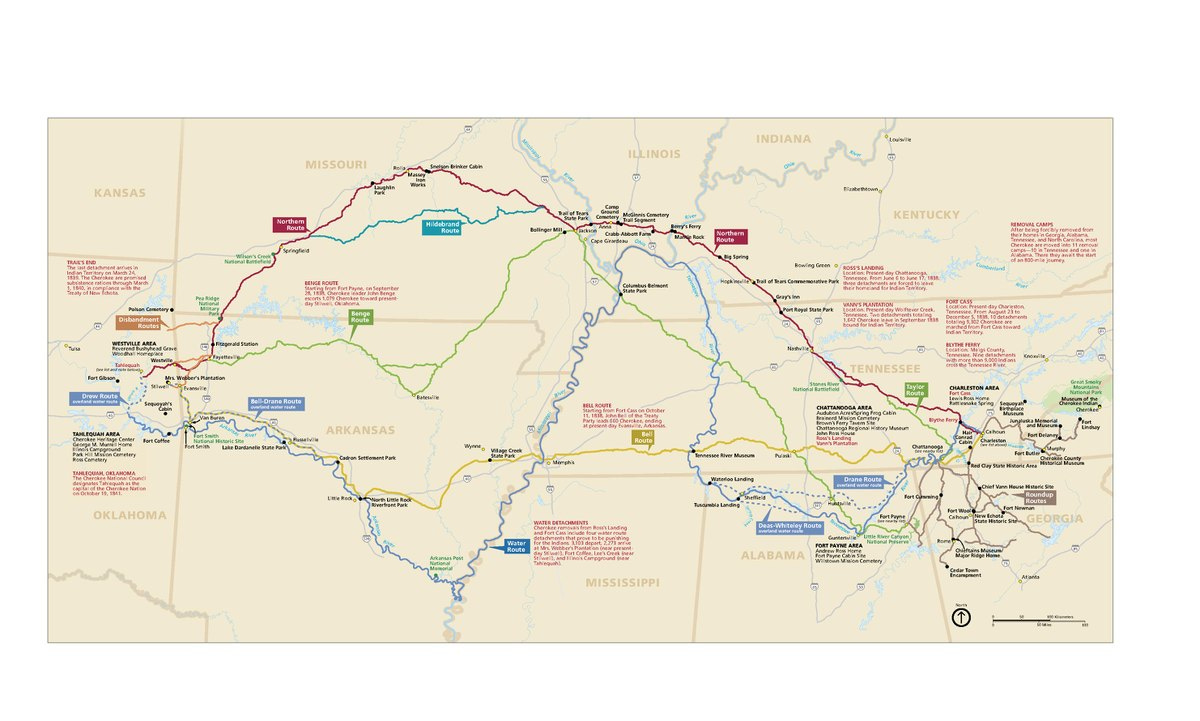

The term “Trail of Tears,” then, is actually a bit deceiving, as it was not a single trail that one tribal group walked. Rather, it is a network of “trails,” most over land, but some over water (through the Gulf of Mexico and along rivers) that five different tribes were forced to take over roughly one decade. These trails all had different starting points in the southeast, ranging from the Great Smoky Mountains of Tennessee and North Carolina in the north to the Everglades of Florida in the south, from northeast Georgia in the east to the Mississippi River in the west. All these trails ended in “Indian Territory,” or what today we call Oklahoma.

The desire for Indian removal from settler land had existed since the colonists first arrived on the continent, but it began to become an official part of US governmental policy under James Monroe. Of course, it would ultimately and famously be Andrew Jackson who put this policy into practice in the most horrific ways imaginable. While the state of Georgia had been fighting for Cherokee removal from their land for years, and while settlers had been stealing and squatting on Cherokee land with no repercussions since the founding of the state, the push for removal amplified when gold was discovered in the North Georgia mountains in 1829. Native peoples were chased from their land, as settlers swept in to hoard the gold. Soon, the state of Georgia began auctioning off Cherokee land to settlers in a lottery. The Cherokee had no say in this matter; they discovered that their land had been given away when a settler showed up at their cabin with a gun, forcing them from their homes.

In 1830, Congress passed Jackson’s Indian Removal Act, which allowed for the removal of Native peoples to begin in its official capacity. Jackson was so committed to this plan that, even when the Supreme Court ruled in Worcester v. Georgia that Native Americans could not be removed without first negotiating a treaty, Jackson continued with the removal. The Supreme Court ruling proved to have no teeth without an executive branch that was committed to enforcing it. Conditions in the east became so bad for the Cherokee that some began to migrate voluntarily. A small, breakaway faction of the Cherokees known as the “Ridge Party,” which did not include John Ross, the Chief of the Cherokee Nation, decided to begin negotiations for removal with the US Government. With the Treaty of New Echota, signed in 1835, this minority faction agreed that the Cherokee would surrender their lands and move westward. In return, the United States would pay them $5 million as an incentive to leave, plus compensate them for the property they left behind and the damages done by settlers, and provide an array of funding for infrastructure and development when they arrived in the West. Most of the Cherokee people, however, had no intention of leaving. Ross gathered the signatures of 15,000 Cherokee people—the vast majority of the tribe—saying that they did not support the treaty and that it was invalid. The US Government refused to accept Ross’s petition.

When Cherokees refused to leave their homes two years later, then-President Martin van Buren sent in federal troops to round up entire families with guns. Roughly 16,000 Cherokee were herded into concentration camps around Fort Cass and Ross’s Landing (modern-day Chattanooga), Tennessee. Beginning in the fall of 1838, detachments of Cherokee began their journey westward. The first detachments left on river barges, but soon a major drought made the waters unnavigable. The remaining Cherokee had to go by foot. Chief Ross petitioned the camp leaders that the Cherokee be allowed to manage their own removal, a condition to which the soldiers agreed. Soon, the Cherokee left the camps and began the walk to the west. They faced horrific conditions, particularly as winter set in. Many starved or died from exhaustion as they were forced to carry on through the harsh winter weather. Most took the northern route of the trail, which headed northward from Chattanooga through Kentucky, west through the southern tip of Illinois and across Missouri, south to Arkansas, and then west to present-day Oklahoma. They traveled over 800 miles by foot. Cherokee Archie Mouse of Tahlequah, Oklahoma, describes the journey his ancestors made:

Where they walked with bare feet on frozen ground a trail of blood marked their passing. Thousands walked, and there were no shoes or blankets even for the old women. There was little food for anyone. Babies were born along the way and nearly all died. Every night a dozen people were buried in shallow graves scraped in the hard ground. By the time they reached Oklahoma, one of every three who had started the trip was dead.

Estimates for the number of Cherokee who died on the Trail vary, ranged as low as 2000 to higher than 4000. But as Theda Perdue, Michael Green, and Colin Calloway argue, “Measuring the disaster in terms of the number of casualties, however, is a mistake. If only one Cherokee had died—or none at all—the dispossession and deportation of thousands of people from their homeland under a fraudulent treaty would still be a tragedy.”

On 16 December 1987, nearly 150 years after the forced removal of the Cherokee began, the US Congress passed Public Law 100-192, which officially designated the Cherokee Trail of Tears as a National Historic Trail, under the administration of the National Park Service. Unlike a traditional national park, which is a self-contained, large swath of land managed by the National Park Service, national historic trails traverse many miles, crossing through towns and cities along the way. As such, the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail is more clearly defined as a growing network of sites that have been granted official status. Today, the National Historic Trail passes through the territory of nine states (Georgia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, Kentucky, Illinois, Arkansas, Missouri, and Oklahoma) and comprises well over 100 sites, including memorials, museums, burial spots, and preserved sections of the trail. The over-2000 miles of the Trail are also marked by signs with a specially designed logo for the Trail of Tears. These sites vary greatly in type, as I will describe, and each is independently managed and/or curated. As a result, although the designation of the National Historic Trail represents the declaration that the Trail of Tears, as an historic event, is worthy of public recognition and historical remembrance, there is no grand vision for how each site along the Trail functions within this network. What exactly, then, is the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail doing? How is this network of memory sites functioning, and what are its potential effects?

In May 2014, I traveled the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail, visiting 22 of the official sites along the route and traversing countless official trail segments—stretches of road built over the Cherokee’s course. My journey was first and foremost a research trip to explore representations of the Trail of Tears in memory spaces across 11 states. Strangely, however, as I was joined by Tibi and our close friend, Caitlin, it was also a new iteration of that other, time-honored, oh-so-American practice: the road trip. This strange ambivalence—the joy of spending time together as we drove across the beautiful country alongside the sadness of the sites we were encountering along the way—was a consistent affective presence throughout the week. This ambivalent affect was similarly represented in nearly every site we visited. We soon came to realize that it is ultimately indicative of the ambivalent relationship that the United States itself has with its own genocidal past. Consistently, this ambivalence illuminated and perpetuated some underlying discomforts: the discomfort of existing as a non-Native subject on Indigenous land; the discomfort of recognizing oneself as a beneficiary of settler colonial genocide; the discomfort of realizing that, simply by living in the place where you were born, you are contributing to the continuation of that centuries-old violence.

What does it mean to travel the Trail today as a non-Indigenous American? Does such an embodied encounter with past violence open opportunities for change in the present? Can the discomfort produced through the essential ambivalence of the Trail be productive? This series of posts explores these questions by looking more deeply at some of the sites we visited on our journey.

Ross’s Landing | Chattanooga, Tennessee

Our journey of the Trail, like that of many Cherokees in 1838, began in Chattanooga, Tennessee. At the time, it was called Ross’s Landing, named for the ferry operated by a Mister John Ross, which crossed the Tennessee River at this point in the early 19th century. A historical marker quaintly states:

[Ross’s Landing] served not only the Cherokee trade but also as a convenient business center for the country. Cherokee parties left from the landing for the West in 1838, the same year the growing community took the name Chattanooga.

The marker makes no mention of how or why the Cherokee left. Rather, it leaves room for the reader to imagine their leaving as consistent with the voluntary journey of other settlers of the period, fulfilling their “manifest destiny” of westward expansion. This erasure of the violence of the Cherokee’s forced removal is one that is replicated across the landscape of Chattanooga.

The historical marker for Ross’s Landing, quoted above, is not the only one in the area. Another, closer to the riverbank, addresses the Trail of Tears with appropriate horror. This marker describes the rounding up of Cherokees, their imprisonment in stockades, and their forced removal to the west, which resulted in the deaths of “about 4,000 Cherokees.” The marker concludes, “The ‘Trail of Tears’, which resulted from the Indian Removal Act passed by U.S. Congress in 1830, is one of the darkest chapters in American history. This historical marker will forever mark the beginning of this ‘Trail of Tears’.” This traditional historical marker is supplemented by several creative and contemporary memorial elements scattered around Chattanooga’s riverfront.

The biggest attraction in the riverfront area is undoubtedly the Tennessee Aquarium, one of Chattanooga’s largest tourist draws, which welcomes more than 750,000 visitors each year, according to its website. The waterfront area next to the Tennessee Aquarium was constructed with the dual and conflicting purposes of being a recreation area for Chattanooga families and a memorial to the victims of the Trail of Tears. This memorial, created by a team of Cherokee artists called Team Gadugh (Cherokee for “Working Together”), was inaugurated in 2005 and named “The Passage.” It is notable that the Chattanooga city government invited a team of Cherokee artists from Oklahoma to design this large and central public space. The involvement of Native voices in the creation of memory space proves often to be the exception, rather than the rule, despite the fact that international norms around transitional justice and memorialization promote the participation of key stakeholders as central to public projects to deal with past violence.

The Passage is a multi-part commemorative space. One component of this memorial is located outside the Tennessee Aquarium. In this plaza, visitors who look below their feet at the paving stones notice this first memorial gesture. Various paving stones feature quotations from an array of historical figures and documents related to the Trail of Tears. One, for example features an 1824 quote from John Ross: “The Cherokees are not foreigners but original inhabitants of America.” Other tiles feature racist language from US American leaders, like Andrew Jackson, as well as excerpts from anti-Indigenous laws, like the Indian Removal Act. Surrounding these tiles are imprints of letters from the Cherokee syllabary, famous as the first Indigenous language with its own written form. Some of the stones also have cracks breaking through them. These cracks are not a result of disrepair, however, but are instead intended to represent the numerous broken treaties between the United States government and the Cherokee people. The thoughtful imagery and symbolic power of this memorial space is belied somewhat by the fact that no signage or marker explains the space to passersby. Indeed, on my visit to the space, few people seemed even to notice the tiles on which they were walking. It serves more as a space of transit than a space of contemplation for pedestrians in the area.

Below this memorial, and closer to the riverside, a more prominent memorial space receives greater attention. On a wall at the base of the Market Street Bridge, an installation of larger-than-life Indigenous figures playing stickball commemorates this traditional Cherokee sport, which also served as a means of solving disputes since pre-colonial times. A set of seven fountains, each squirting water high into the air, represents the Seven Sisters, the common name for the Pleiades Constellation, which is the cosmological origin space of the Cherokee, according to Cherokee legend. The most visible memorial component of The Passage, however, is certainly the massive set of “weeping stairs,” a tiered waterfall installation that, according to the website VisitChattanooga.com, represents “the tears shed as the Cherokee were driven from their homes and removed on the Trail of Tears.” The wall alongside these weeping stairs features seven ceramic disks, each six feet in diameter, and each representing a different clan of the Cherokee.

Unlike the memorial plaza above, the weeping stairs do not go unnoticed by passersby. Quite the contrary, these stairs are a gathering space for locals and tourists alike, especially during the summer months. These visitors are not necessarily visiting the space to remember and honor the Cherokee, however. Instead, the stairs serve as a playground for countless children, cooling off from the summer heat. Indeed, during our visit in May 2014, the steps were filled with children in their bathing suits, playing in the water, running up and down the stairs. The stairs may have been weeping, but the children running up and down them were laughing and yelling with joy—a fascinating juxtaposition given the intent behind this memorial space.

Visitors are not necessarily unaware of the symbolism behind the space, even as they use it as a site of recreation. One local blog called Play Chattanooga offers suggestions for fun things to do in the Chattanooga area. The blogger includes one entry, entitled “The Passage (The Water Steps),” in which she writes:

Here’s another park our family has affectionately nicknamed. It is aptly named “The Passage” because it is a link from downtown (in front of The Tennessee Aquarium) to the river and because it is a memorial for the beginning of the Trail of Tears. We just call it The Water Steps because we tend to take for granted the beautiful Native American art and painful history, and we just love to play there. Picnic? Yes. Swimsuit? Yes. Cost? None. Author’s Rating? Five out of five stars! […] In our family’s opinion, this is the perfect Chattanooga place to spend a hot summer morning.

The blogger acknowledges the “painful history” evoked by the weeping stairs, as well as the fact that her family takes it for granted, revealing a strange ambivalence that is not unique to this memory space. This blogger knows what the stairs mean. In some way, at least, the memory of the Trail is something she acknowledges. The behavior of her and her family, however, stand in contrast to the sorts of behavior one would imagine at a memory space.

“The Passage” in Chattanooga is not the only memory space to be used as a site of recreation. The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin serves as the background for countless social media profile pictures, and even dating profile pictures—a fact that has been derided in many news stories. Such “misuse” of the memorial inspired Israeli artist Shahak Shapira to create the online art project Yolocaust, in which he superimposes the selfies visitors take at the site onto horrific photographs from Holocaust death camps. Similarly, controversy erupted when tourists started using the 9/11 Memorial in downtown New York City as a picnic site or a playground. These two examples demonstrate that treating a memorial space as a recreational area is not at all unique to “The Passage.” The difference, of course, is that these other two examples provoked outrage from news media and the public. No similar outrage has emerged relating to “The Passage.” It is unclear exactly why such practices at some memory spaces are seen as “disrespectful,” while at others they are viewed as good family fun, but it most certainly has something to do with the fact that the constituency of people who feel invested in and protective of the memory of the Holocaust or September 11 far exceeds that of those defending the memory of Native atrocities in the United States. In fact, controversies arising with regards to the appropriate use of memory space are not, in themselves, a bad thing. These controversies can be a part of encouraging conversations about how contemporary publics should relate to and understand a violent past. In the process, these debates ensure a space within the public sphere for such memories. The fact that no such controversies have occurred in Chattanooga perhaps more than anything demonstrates the non-saliency of Native genocide as a topic that provokes an emotional response in non-Indigenous Americans. Throughout the Trail, this wavering relevance of settler colonial genocide to non-Native groups is one that creates both opportunities for engagement and for erasure in sites all along the Trail.

To be continued…

Thank you for beginning to share Chapter 6 with us! It definitely deserves to see the light!

looking forward to reading more